Who's Who at CIMAM with Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani

Who's Who with Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani

CIMAM member and Curator of the National Pavilion of Timor-Leste at the 2026 Venice Biennale.

Could you tell us about your background in contemporary art and your trajectory as a curator?

I’ve been surrounded by art for as long as I can remember. My great-grandfather was an Impressionist painter, and his works were part of my everyday environment growing up. I was very fortunate in that sense—art has always been a quiet companion in my life. However, my true engagement with contemporary art began when I moved to Thailand 25 years ago. It was a pivotal shift. I started by learning the Thai language, then gradually immersed myself in Thai culture and philosophy. That journey led me to pursue two Master’s degrees—one in Singapore and another in London—focusing on contemporary Southeast Asian art and culture. Since then, I’ve dedicated myself to researching Southeast Asian contemporary art through fieldwork, teaching, writing, and, of course, curating.

What are the key milestones that have shaped your curatorial practice, and how has your work evolved over time, particularly in relation to Southeast Asia?

From a research perspective, significant milestones in my curatorial journey have been the many field trips across Southeast Asia. More recently, I’ve had the opportunity to visit Timor-Leste, which has opened up new perspectives. The encounters—with artists, researchers, and everyday people in markets, homes, or studios— have further informed my curatorial approach, particularly in foregrounding the minor voices that persist alongside mainstream history.

In terms of practice, the exhibition Architectural Landscape: SEA in the Forefront (2015) at the Queens Museum in New York, was really important. It was eye-opening to see how different it felt compared to previous projects I curated in Manhattan. In Queens, there was a shared language—a mutual sensitivity around themes like displacement, migration, and minoritized voices—that mirrored my research in Southeast Asia, which made me understand the importance of bridging cultural differences to be able to talk to each other.

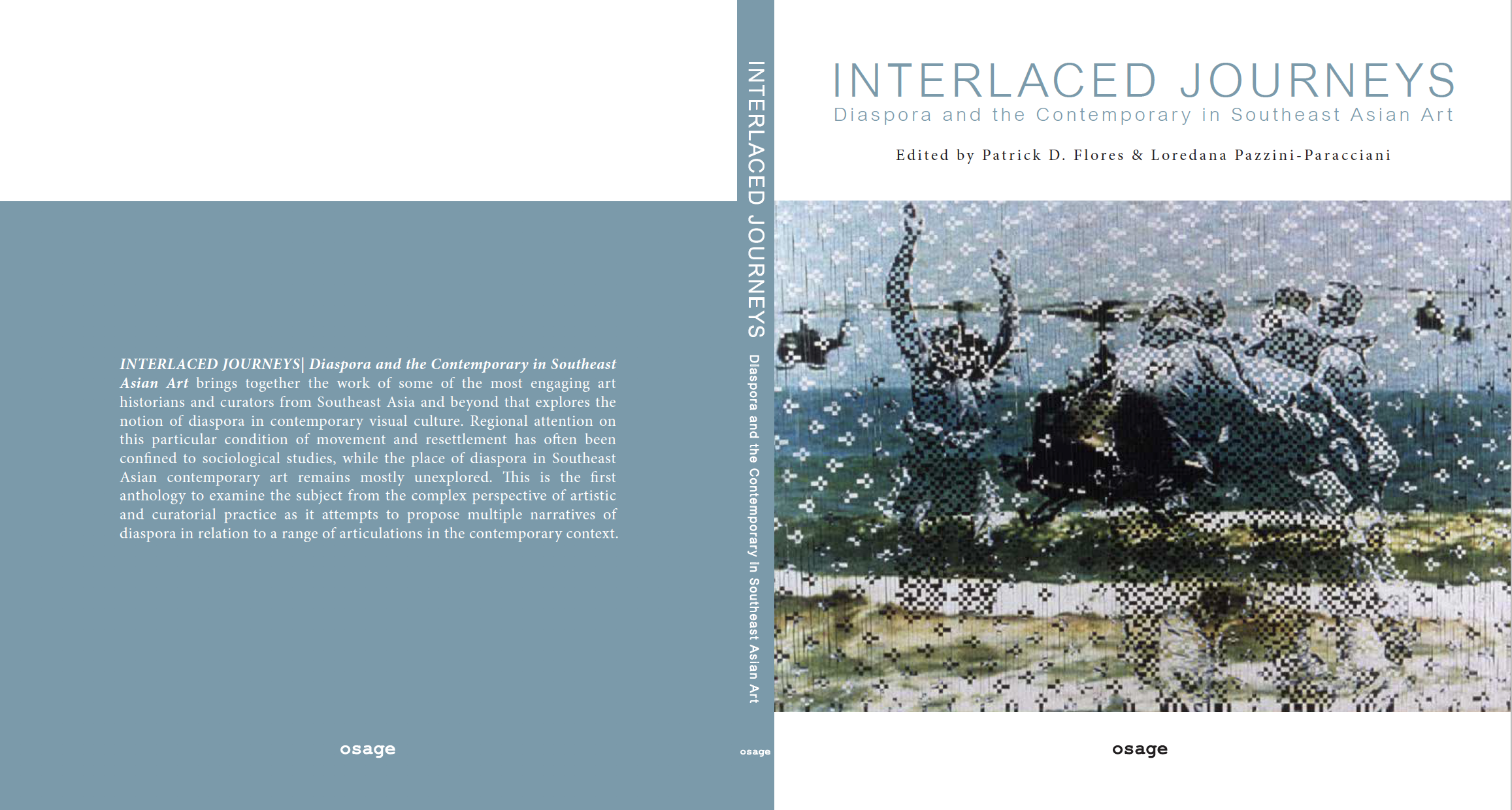

Co-editing the book INTERELACED JOUNREYS |Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art (Osage Art Foundation: 2020, Hong Kong) with Patrick Flores was another important milestone. It allowed me to work alongside leading scholars and thinkers from the region, not in the exhibition format but purely academic. It was a truly collaborative experience that deepened my commitment to telling layered, place-rooted stories from Southeast Asia.

As an independent scholar and curator specialising in Southeast Asian contemporary art, your work frequently engages with urgent sociopolitical issues in the region. Could you share some recent or particularly meaningful projects you’ve developed in this field? What kinds of collaborations or institutions do you typically engage with to bring these narratives to life?

Indeed, dealing with urgent socio-political issues in Southeast Asia requires close, sustained collaborations with artists and communities to bring attention to topics that are often underrepresented or marginalized. On this note, one of the most profound and meaningful experiences with Vietnamese communities was during the collaboration with late Dinh Q. Lê. Together, we developed a project titled Pure Land (2019), which explored the devastating and long-lasting effects of Agent Orange on the communities. For this project, we engaged with people in Saigon—listening, discussing, and bearing witness to their stories.

Reaching out to the younger generations is also very important to me. For the project Sinking and the Paradox of Staying Afloat (2024) several Southeast Asian artists and I worked together to talk about climate change. To do so we involved students from Silpakorn and Chulalongkorn Universities, to foster an intergenerational dialogue around climate anxiety, responsibility, and agency.

On the other hand, for the exhibition Disobedient Bodies: Reclaiming Her (2025), which featured eight female artists from across Asia, our intention was to reach out and collect a multitude of female voices from different cultural groups on themes of gender reclamation. In Singapore, where the exhibition was presented, we collaborated with CARE to empower and create awareness throughout the younger generations.

You advocate for a counter-hegemonic and non-Western-centric approach to curating politically and socially engaged art in Southeast Asia. From a curatorial perspective, how do you navigate this space? What strategies or methodologies do you use to centre local epistemologies, lived experience, and community knowledge in your exhibitions?

One essential part of my process is the ongoing dialogue with the communities involved in the research, and with the artists. My exhibitions typically take at least a year to develop, precisely because I initiate conversations early on. Together, we shape the project’s direction, discussing its themes, approach, and context in a way that ensures mutual understanding and collaboration. This long-term engagement allows the work to grow organically, and for trust to be built—something I consider fundamental in curating socially and politically sensitive narratives. The priority for me is always to center the communities and artists, and to allow their stories to lead.

You’ve recently been appointed curator of the National Pavilion of Timor-Leste for the 2026 Venice Biennale. Could you tell us more about your research experience so far, your impressions of the local art scene, and how this is informing your curatorial vision for the pavilion?

Previously, I engaged with Timorese culture through my collaboration with Maria Madeira, who represented Timor-Leste at the 2024 Venice Biennale. She was one of the eight female artists featured in my exhibition Disobedient Bodies. However, this recent trip was an eye-opener for me. Timor-Leste carries a deeply traumatic past—violence and occupation have left indelible marks on its collective memory. And yet, what moved me most was the resilience of its ancestral traditions, which have endured despite near annihilation.

The contemporary art scene is still emerging. There are no formal art schools, and access to materials is limited. But what they may lack in infrastructure, they more than make up for in creativity, energy, and a powerful drive to learn, create, and share. I encountered a vibrant community of artists and makers—curious minds eager to explore contemporary practices while remaining deeply rooted in their cultural traditions. There is a desire not only to preserve this heritage, but also to translate it into visual languages that can reach beyond their borders. This experience has deeply inspired and informed my work for the Timor-Leste Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. It has reinforced my belief in art as a living, breathing force—capable of holding memory, sustaining identity, and opening new pathways of connection with the world.

The history of Timor-Leste is quite unique, shaped by Portuguese colonialism and marked, despite the country’s small size, by extraordinary linguistic and cultural diversity. Could you speak about how this complex and multilayered history, including the presence of numerous Indigenous languages and ethnic groups, is shaping your curatorial approach for the Biennale?

Absolutely. In Timor-Leste, there are 32 identified dialects, alongside two official languages—Tetum and Portuguese—and two additional working languages, Bahasa Indonesia, inherited from the occupation period, and English. Communication can appear complex, yet it flows remarkably well. There’s a certain solidarity, a sense of fraternity, that binds people—whether through shared dialects, regional identity, or lived experience.

What fascinates me is how storytelling, oral history, and visual symbolism have long been central to Timorese modes of communication. These are the vessels through which ancestral knowledge is transmitted—from personal status and family legacy to communal rituals and major historical events. I’m still in the early stages of developing the Pavilion, but I can already sense its shape emerging. It will likely feature a small group of artists across generations, working across a range of mediums to explore how language—spoken, written, or remembered—continues to shape cultural identity in profound and poetic ways.

As someone deeply involved in research and publishing, including your editorial work in various journals, how do you see the role of publishing in supporting curatorial practice and fostering critical discourse? What value does writing bring to your work as a curator, and how do these two spheres—curating and publishing—interact in your practice?

Writing, editorial work and publishing are essential for me. They are not only tools of documentation but also vital means of entering a broader conversation—one that includes other scholars, researchers, and practitioners. Through this exchange of ideas, we challenge assumptions, learn from one another, and open up new avenues for inquiry. It is especially important for Southeast Asian studies. Southeast Asia is a vast and culturally diverse region. Each country holds its own unique historical trajectory, yet there are also shared experiences, patterns, and echoes across borders. This makes it especially important to think across disciplines and to embrace interdisciplinary approaches.

You became a CIMAM member in early 2024. How have you enjoyed and engaged with the community and the platform so far, and how would you like to benefit from it in the future?

I have participated in several online conferences, all of which I found intellectually stimulating and enriching. These gatherings have offered valuable insights and connections, even from a distance. Looking ahead, I hope to attend the annual meeting in 2026, schedule permitting with my work on the Pavilion. It would be a meaningful opportunity to connect in person with this vibrant and creative community, to share ideas, and to further engage with the ongoing conversations shaping our field.

Lastly, could you recommend a reading for CIMAM’s members?

Lately, I’ve been deeply engaged with the book Revolusi by historian David Van Reybrouck a remarkable work grounded in meticulous research on the history of Indonesia. Its depth and detail have not only enriched my understanding of the region but also prompted me to reflect more critically on the history of Timor-Leste and its path to independence. Reading it has offered valuable historical context and comparative insights that are proving especially meaningful as I continue developing the Pavilion project.