"The Artist as Ecologist" by Filipa Ramos

Interview with Filipa Ramos, CIMAM Member and author of The Artist as Ecologist, published by Lund Humphries on 14 October 2025.

The book is included in the CIMAM online bookshelf through our ongoing collaboration with Lund Humphries, offering CIMAM members a 25% discount on all titles. Although The Artist as Ecologist is currently sold out, copies will be available again in January. CIMAM members can already use their discount for pre-orders via the Members Only section!

Filipa Ramos is a curator and writer whose work intersects art, moving images and ecology. She is a Lecturer on the Master's Programme at the Arts Institute of the Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz, Basel, where she leads the Art and Nature seminars, and Artistic Director of Loop Festival, Barcelona. Her publications include The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish (as co-editor) and Animals (as editor). By merging curatorial practice, writing and transdisciplinary research, Ramos has expanded the discourse of Art History towards an ecological sensibility, encouraging museums, curators and artists to envisage art as a catalyst for social and environmental change.

Your book looks at how artists are engaging with ecology and addressing climate change in their work. What motivated you to explore this topic?

I have been obsessed with animals and all other forms of nonhuman life since I was a child. Over the years, I turned this love into work and I started putting most of my writing and curatorial energy into it. The Animals book I published in 2016 (Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press) was probably the first manifestation of it, and it emerged from my PhD research on time-based media and zoological gardens. This was followed by the whole Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish festival, which I have been curating with Lucia Pietroiusti since 2018, first at the Serpentine in London and now independently, as well as all the shows and texts that emerged from our long-lasting collaboration.

During these last years, I found myself increasingly drawn to artists whose work was not simply about nature or climate change, but tried to connect on a more profound way with ecological processes, more-than-human lives, and to engage with infrastructures that support or destroy them. These practices made me realise they weren’t a mere strand of contemporary art but one of the main areas where new imaginaries around climate, responsibility and coexistence were being experimented.

The Artist as Ecologist was also motivated by a frustration with two extremes: on the one hand, a didactic “climate illustration” where art and theory became sort of posters for already-known environmental tragedies and facts; on the other, a purely formal discourse that ignores the material and political conditions in which artworks are made. I wanted to write with and not about the artworks (recalling Trinh T. Minh-ha’s call for giving up aboutness in her documentary Reassemblage), but with an awareness of the worlds they touch: land, water, animals, labour, extraction, pollution. The Artist as Ecologist is an attempt to honour that complexity and to show how artists are reconfiguring what ecology can mean and do today.

In The Artist as Ecologist, you address both ecology as a subject matter and ecology as a practice. How do you think these two approaches contribute to education and public understanding of the climate emergency?

Ecology as subject matter is the most obvious layer: works that represent and reproduce glaciers, forests, oceans, extinction, pollution. These offer images, narratives and affects that can make the climate emergency tangible, especially when scientific language feels distant or complicated. They can give a face and a rhythm to processes that are otherwise abstract: melting, migrating, eroding, contaminating. This is of course crucial for education. But often they are repetitive, derivative and utterly depressing, as they show and say what most people by now know.

Ecology as an artistic practice goes further by acknowledging that the ecological crisis is an aesthetic crisis (as it concerns our sense of beauty and harmony which influences the way we shape the world, the materials we use, the species we favour and fear and so on). It asks how something is made, with whom, with what resources, at what speed, and with what consequences. But it also tries to adopt collaborative, site-responsive, low-carbon, or more-than-human methods that reveal how ecology is not just a theme but a method, a way of doing things. For students and wider publics, this can be transformative: it shifts the question from “How can art represent climate change?” to “How can our ways of working, learning and exhibiting provide concrete examples of less extractive and more attentive practices?” Education, in this sense, is not only about acquiring knowledge; it is about practicing different modes of relation.

Many of the artists you discuss embody a renewed closeness to the land and highlight the growing relevance of performance and time-based media in ecologically engaged art. How do you think art can help us reimagine our relationship with the natural world and cultivate new forms of attention, empathy, and connection?

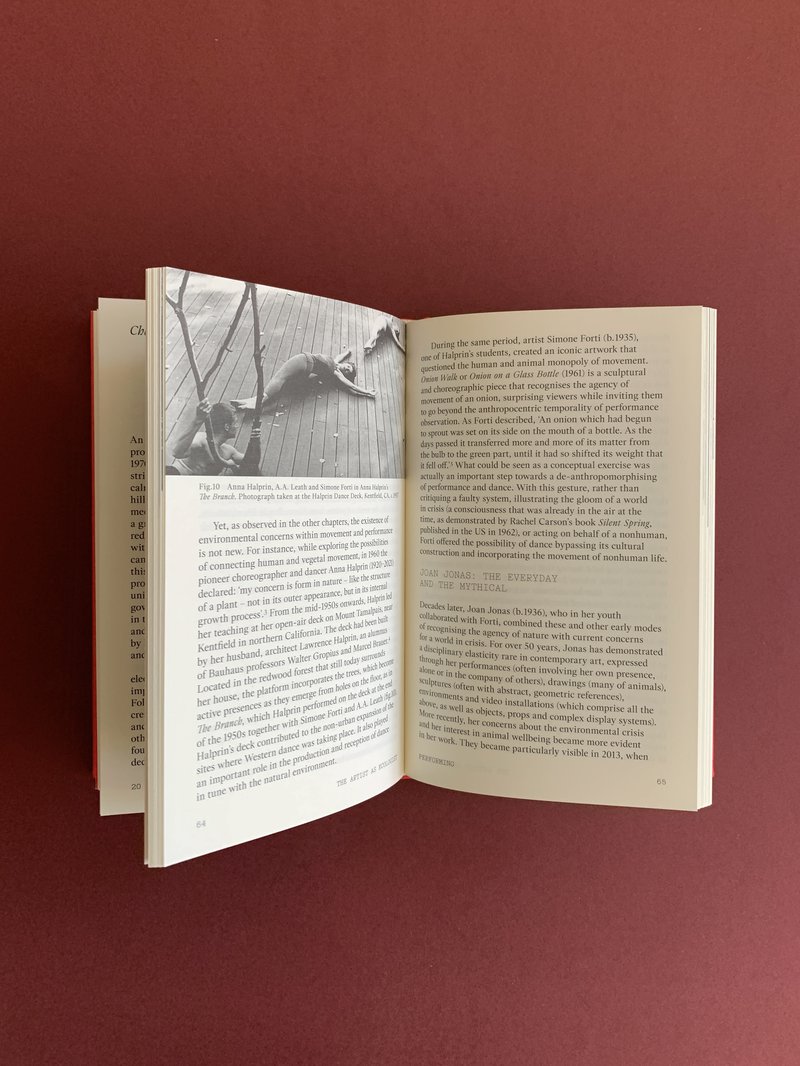

Performance and time-based media are particularly suited to ecological thinking because they unfold in duration and in relation; they are live. They require us to stay with a situation, to inhabit its tempo, to accept that things are changing even as we watch them, and also to go way beyond representation. When artists work with landscapes, animals, the weather, or local communities through film or performance, they often install a shared temporality (and install themselves within it): the time of tides, of growth, of decay, of migration. Such temporal immersion is important to transform embodied, inherited, epigenetic habits and to install new rituals and approaches to life. Simone Forti, who is probably the artist who has influenced me more to think about ecology and relationality, often declared her desire to “be a vertebrate amongst others” and this is exactly the kind of experience of transformation and humbleness that performance, dance and other corporeal, time-based practices can propose.

Art can also dislocate habitual hierarchies. By revealing how a river is worth as much attention and care as a human, or by letting a nonhuman presence determine the structure of a work, artists model relationships that are not merely based on empathy, similarity but on coexistence. They create situations where viewers are asked to listen, to wait, to adjust, rather than to immediately understand or consume. These new forms of attention—slower, less possessive, more open to uncertainty—are essential to rethink our relationship with the so-called “natural world” not as a resource but as a community of beings and processes to which we belong.

What would a truly ecological model of exhibition-making look like to you?

That’s a very hard question. Models and formats should be continuously evolving and follow no prescriptions otherwise, they become obsolete in no time. Right now, I’d propose that a truly ecological exhibition would not just show but would behave ecologically. This may sound too poetic or animistic, but it concretely proposes to think the exhibition as an ecosystem rather than a product. Materials would be chosen for their lifespan and afterlife: What happens to the walls, the screens, the crates, the catalogues? Works and artists would travel less and stay longer; collaborations would be developed slowly, perhaps over several years rather than a single season. Local skills, agents, crafts and infrastructures would be prioritised (also to assure a fair redistribution of resources), and international connections would be cultivated without defaulting to constant air travel.

A truly ecological model cares about the conditions of those who build, guard, clean, mediate and maintain it, not creating an uneven balance between international artists “making” artworks and local craftspeople “producing” them without being acknowledged. It values accessibility, fair pay, and the emotional and temporal economies of everyone involved. And, crucially, it sees audiences not as “visitors to be counted” but as co-makers in a shared, ongoing exchange. In such a model, the most meaningful impact may not be the spectacular opening, but the quieter, sustained relationships that endure once the show is over.

To what extent can contemporary art institutions not only support artistic creation around ecological themes, but also lead by example through their own operational and ethical practices? In this regard, how do you see resources such as CIMAM’s Toolkit on Sustainable Museum Practices contributing to this transformation?

Institutions have an enormous potential to move from supporting and illustrating ecology (ie. Making shows and programmes about the environment and its communities) to embodying certain values. Commissioning and exhibiting works on climate is of course important, but if the building runs on crazy amount of fossil fuels, if staff are overworked and underpaid, or if every project relies on frenetic global mobility, if its café serves animal-based products and processed food, there is a huge dissonance that audiences increasingly perceive. Leading by example means aligning programming, governance and operations: energy use, procurement, travel policies, food, banking, partnerships – all of these are part of the institution’s ecological footprint.

Resources like CIMAM’s Toolkit are valuable because they provide concrete, shareable frameworks. They translate a rather vague desire to be “sustainable” into specific questions and steps: how to measure emissions, how to rethink loans and shipping, how to create internal cultures that support care, accountability and transparency. They also normalise the idea that sustainability is not an add-on but a core responsibility. The most interesting institutions are those that treat these tools not as a checklist to comply with, but as a starting point for deeper transformation, which they adapt to their specific spaces and contexts, informed by the artists, people and spaces they work with.

We are currently witnessing a growing attention to Indigenous knowledge in discussions around sustainability. In what ways can such knowledge be meaningfully integrated into museum practice?

I am not the best person to answer this question: I am a white, Portuguese person and most certainly at least a bit of my DNA declines from invaders that, still today, the country where I was born calls “discoverers.” I would start from this acknowledgement and, with humbleness, recognise that Indigenous knowledge is not a “resource” to be integrated, but a living set of practices, cosmologies, voices and sovereignties held by specific peoples. This is why in the “Claiming” chapter of The Artist as Ecologist, dedicated to Indigenous intersections with ecology, I tried to integrate as many statements and first-person declarations as I could (to the point that the book's editor, Michela Parkin, complained that she couldn’t “hear” my voice and stances in it). I tried to make the space that I had been given to the voices of those who should be heard.

Meaningful integration also evolves with long-term relationships, forms of co-authorship and shared decision-making, rather than occasional invitations or thematic exhibitions. It requires people and institutions to ask: Who defines the questions? Who controls how knowledge is shared, documented and archived? Who benefits, materially and symbolically?

In practical terms, this can mean establishing advisory councils, co-curated programmes, and sustained partnerships with Indigenous communities; rethinking collection policies and restitution; revising labels and narratives so that they acknowledge histories of violence and dispossession; and ensuring fair remuneration and proper crediting for intellectual and artistic contributions. It also means being ready to be challenged – for example, around protocols of access, photography, display or conservation that may conflict with Western museum norms.

Crucially, engaging with Indigenous knowledge, and integrating within the operativity of places and structures should transform the institution itself: its understanding of land, time, ownership, responsibility. When museums allow these encounters to unsettle their assumptions, rather than just diversifying their content, they become places where different worlds can meet without one claiming the right to speak for all.