Museums in Dialogue: Asia and Africa

A conversation with Raphael Chikukwa, Executive Director of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, and Suhanya Raffel, President of CIMAM and Director of the M+ Museum in Hong Kong.

Originally published in Spanish by Exitmedia in the Outlander section of EXPRESS magazine, on July 3, 2025, under the title "Museos en diálogo: Asia y África." Written by Diana de la Cruz. Available for consultation here.

Summary

Last week, it was announced that the 2026 CIMAM (International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art) Annual Conference will be held for the first time in an African country: Zimbabwe. It has taken over 60 years—CIMAM was founded in 1962, and the 2025 edition will be its 57th—for this to happen: for the nearly 800 museum directors and curators who make up the organization to not only turn their attention to the African continent, but to take effective action that enables the emergence of voices and perspectives that have largely been overlooked until now. Marking a step toward the true de-Westernization of the international museum landscape, the selection of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, with its main location in Harare and branches in Bulawayo and Mutare, as the host institution for the 2026 Conference represents a milestone in CIMAM’s history.

Taking advantage of the announcement, and just months ahead of the 2025 Conference in Turin titled Enduring Game: Expanding New Models of Museum Making, I met with Raphael Chikukwa, Executive Director of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe since 2010, and Suhanya Raffel, President of CIMAM and Director of M+ in Hong Kong, to discuss the current state of museums in China and Zimbabwe and their roles in the cultural processes. Both institutions, the first one a key reference for modern and contemporary art in Southern Africa, and the second one the largest museum in Asia dedicated to contemporary art and visual culture, represent two fundamental poles for understanding the challenges and opportunities facing museums in dynamic and diverse cultural contexts.

Diana de la Cruz: In recent years, there has been an intense debate around the need to redefine what a museum is, moving beyond traditional, conservation-centered views and toward more critical, participatory, and socially engaged approaches. I’d like to start by reflecting on how we currently understand museums, their evolving nature, their role in cultural and social transformation, and the many ways they operate and define themselves. Based on your own paths and contexts—China and Zimbabwe—how would you define a museum today? What makes each museum a singular space, with its own logic and purpose?

Suhanya Raffel: I'll jump in and, if you're okay with it, I'll start directly with this idea: museums are like people, no two are the same, and that’s precisely the most beautiful thing about museums, just as it is about people. The fact that they are not the same is part of the DNA of our institutions. Museums are in constant dialogue and exchange, and there are spaces for shared interests and values. From within museums, we work with communities and the local public, but also with international audiences and colleagues. Like people, institutions are living organisms, in continuous transformation and evolution. That’s why museums are wonderful, because today they are something very different from what they were ten, or even fifty, years ago.

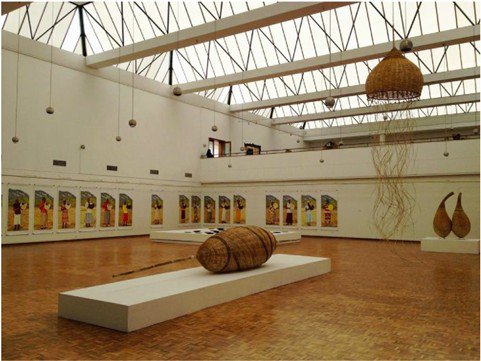

Raphael Chikukwa: To add to Suhanya’s point, museums also allow us to celebrate our diversity and the fact that we will never be the same. Whether we are in Asia, Africa, Europe, or Latin America, we are all different, but that diversity is precisely what unites us. As she said, museums are living organisms that evolve constantly, and what they were in the 1950s is nothing like what they are today. They continue to grow and change in color, shape, and scale. You can see this clearly in places like the Middle East or Hong Kong, where museum architecture has transformed dramatically over time. I think of a museum I visited in Hong Kong in its early years, designed by a Swiss architect; the Louvre in Abu Dhabi; or even the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, founded in the 1950s, and I always say that Peter Oldfield, the architect of this last one, was ahead of his time because 75% of the main building is naturally lit. He was already thinking about sustainability long before the conversation turned to how museums can be sustainable today.

Now we want the West to also move toward the Global South, to come, to see, and to understand it from a new, situated perspective.

DC.: What a visual metaphor, thinking of museums as people, and how interesting it is to see them that way to understand their diversity and uniqueness. Considering that each museum reflects its own geographic and cultural context, could you share what the institutions you lead are like, so that those of us who are not familiar with the Chinese and Zimbabwean contexts can get a sense of them? And going back to the idea of museums as people, how would you say museums relate to one another, both locally and internationally? What role do networks and collaborations play in their growth and visibility?

RC.: The National Gallery of Zimbabwe (originally called the National Gallery of Rhodesia) was founded in 1957, and Frank McEwen, a British national living and working in Paris, was appointed its first director. It opened with an exhibition titled From Rembrandt to Picasso, the largest exhibition of European masters to travel from Europe to the African continent in the 1950s. Thanks to McEwen's connections to Europe, he managed to have some exhibitions from Zimbabwe travel to Paris, London, and New York. This was a major achievement for the National Gallery, and what we want to do, what we have been doing, is to follow in his footsteps, continue his initiative, and keep bringing Zimbabwean art to Europe. In fact, with this idea in mind, the Zimbabwe Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was inaugurated in 2011, a participation that continues to take place with each new edition. And while this has allowed us to maintain that visibility, today we have a new goal: for all these years, we have taken Zimbabwean art to the world, but now it’s time to bring the world to Zimbabwe. This is the role the National Gallery wants to play, to ensure that the global art and museum ecosystem goes to Africa and understands Africa from its own context. This will happen next year, with the CIMAM 2026 conference taking place in Zimbabwe, for the first time in a country on the African continent. And I trust this is also what has been happening with When We See Us, the exhibition curated by the recently deceased Koyo Kouoh, which has been traveling across Europe. This is another way of continuing to make African art visible on the international stage. That is why museums keep growing and changing, often depending on who is leading them and the networks they are grounded in and connected to. What we seek is to expand our own networks in order to better understand ourselves within this ecosystem.

SR.: I believe something fundamental, which underlies everything Raphael has said, is that our museums are modern and contemporary art museums, and what we share is the language of art, of creative expression, and of culture within our different contexts. And exchange, seeing and learning, is essential to that. We are also connected by the fact that we work with artists and build collections, each of a different kind, but collections nonetheless. As institutions, we are constantly educating and learning from our audiences. Now, relationships are bidirectional, it’s no longer a one-way street. The world has learned how important and valuable it is to be open to dialogue, collaboration, and exchange.

D.C.: In relation to that, I’d like to know how a balance is achieved between promoting artists and local creation, and incorporating international art into the museum’s programming. How are both aspects integrated—if they can even be considered separate—in your museums? In what ways are relationships with national artists established and nurtured from within the institution itself? I recognize that it’s a complex challenge to provide space and visibility to local production while also staying connected to global trends and dialogues in the art world.

R.C.: For us, it’s very important to know, and to acknowledge, where we come from and our history. Here, I’d like to talk about the International Congress of African Culture, founded by McEwen in 1962—the same year that CIMAM was founded, just to give some context. When it took place at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, museum professionals from Europe, America, and Africa were invited, and among the attendees, in addition to prominent cultural figures from Ghana, South Africa, Nigeria, Mozambique, and other African countries, were people like Alfred Barr, founder and director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Roland Penrose, director of the ICA in the United Kingdom. A few years ago, during a residency I did at MoMA, one day while talking about the relationship that was established when Barr visited Zimbabwe, the museum showed interest in learning about the National Gallery and its archives. That interest led to two trips to Zimbabwe and to the development of an African art exhibition project at the New York museum, which will be presented next year, featuring a significant collection held by the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, including works by modernists from Nigeria, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Ghana, among others. What I want to say is that sometimes history connects us, and these parallel histories are key to the development of projects, they are what can bring us into contact and give rise to something much bigger than we imagined. Especially for us as curators, exploring the archives and finding ways to amplify them for our audiences is essential, and what will be seen in the MoMA exhibition will be, among other things, what history does, what it is, how it works, and how we can learn from it.

What does this have to do with my reality? I know there is art in Asia, we are a living culture, full of artists doing all kinds of things, but why isn’t it here?

S.R.: I think that’s been pretty well answered, to be honest, I’m not sure I have much more to add, except to say that this is a brilliant example of how institutions can work together, and of the very different, sometimes unexpected, places where knowledge resides. The work of our institutions, each within its own context, is precisely that: to research and to share.

R.C.: And exhibitions, congresses, and educational programs are part of this ecosystem; they help educate us as researchers, as museum directors, as curators, and help us learn from the archives, the collections, and the artists we work with.

S.R.: We are always working with local, regional, and international artist, it’s something that flows naturally, it’s not about percentages or specific numbers, and it happens quite organically.

R.C.: Also, as I was saying earlier to Suhanya, we are now cutting that umbilical cord, breaking that link that for years worked in only one direction: us moving toward the West. Now we want the West to also move and come to the Global South, to see it and understand it from a new, situated perspective.

D.C.: Without a doubt, that shift in perspective is extremely important, especially because in Europe we often tend to think that the flow of knowledge and culture moves in only one direction. But it’s clear that reality is much more complex, and that there is a constant, multidirectional exchange that crosses and connects everything. How is that relationship between global knowledge and local or regional perspectives established?

S.R.: I can give a very clear example of this. When I was studying Art History at the University of Sydney, the art history we were taught was basically European and North American, it had practically nothing about Australian art, and even less about other regions. In Australia there are many migrant communities and a strong diaspora. Thinking about my own path, and the kind of museum I wanted to work in, to be part of from the beginning, I realized that if I wanted change, it had to come from me, because no one else was going to do it. Sitting in class I thought, “What does this have to do with my reality? I know there is art in Asia, we are a living culture, full of artists doing all kinds of things—the only Asian art we were taught was historical, premodern art—but why isn’t it here?” We were a very small group of people who became aware that things couldn’t continue like that, that we couldn’t keep waiting—this was a long time ago, by the way—and that we had to “do something.” And it is only now, in the last fifteen or twenty years, that this work has started to become visible.

R.C.: Something similar happened to me when I studied Art History and when I delved into the archives of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe. There I found episodes like the founding of the Cyrene Mission in 1948 by Reverend Paterson, who aimed to integrate art as an essential part of the spiritual and educational training of young Africans; the arrival of McEwen in Zimbabwe in the late 1950s and his idea that there was no art education in Africa; or the creation of the Tengenenge Art Center in 1966, just a few kilometers from Bulawayo, to “teach Africans how to paint.” When you learn about this, you understand why it is necessary to revisit and retell our own history. Before painting on rocks, Africans were already painting on their bodies, and, as in Aboriginal art in Australia, Māori art in New Zealand, and that of many other colonized contexts, if one looks closely, one finds numerous examples of artistic practices that date back thousands of years. Rock art is clear proof that there was already a pictorial tradition in Africa.

On the other hand, saying that there was no architecture in Africa, or that museums didn’t exist, is something we need to reconsider. The architecture of Great Zimbabwe is one of the few surviving monumental African structures, along with the pyramids of Egypt. The shrines, the palaces of our kingdoms, were museums. And there is also a long sculptural tradition, you only have to look at the Benin bronzes, or so many other objects that are now kept in European museums. Sculpture, painting, and architecture have always been there, which is why it is necessary to explore that history and tell it from our own perspective.

D.C.: And how do you think this has changed in recent years? In what ways is the inclusion of these concerns and narratives being promoted within museums? But also, what would you say are the main themes contemporary artists are addressing today?

It’s about thinking transversally and from different perspectives about the institution: what we need and how we can address that need.

S.R.: I think the fact that we are sitting here is a reflection of the change that is happening in museums. Besides, the contemporary art museum is not something static; it is constantly evolving, and working with artists involves exactly that, constant change. They bring different perspectives, they put new topics and materials on the table. For me, this dialogue generates some of the most stimulating, interesting, and intelligent conversations that can happen within an institution, often in unexpected ways. That’s also what makes it particularly enriching, reflective, and provocative. Today, artists’ practices are very diverse, among other reasons because they are deeply connected to the world we live in and address issues that affect us all. These are practices committed to society and politics, they are radical, bold, experimental… I would say there is a great deal of generosity in creative action and a conviction that it matters. Art is the way we remember who we are.

R.C.: Artists are storytellers. And those stories come from the experimental, the historical, the archives, and the environment. Especially today, in Africa, found objects have become a means to tell stories, and what some might see as trash, others use as a tool and a starting point. Their narratives educate those of us working in museums, as well as students, environmental activists… they are political and social narratives. All of this fits into a global or geopolitical context that changes every minute. That is precisely the exciting work we do, I mean, exhibitions constantly surprise you, just like working with artists. They create new works that we then present to the public as exhibitions. But sometimes, even before reaching the public, their work has already surprised us, their various languages, whether it's photography, video art, installations, performance, or many other media.

You can never do it alone. Bringing people together and fostering collective thinking can make a big difference.

D.C.: Could you give us an example of a project, initiative, or activity you’ve launched at M+ or the National Gallery that has shaken the foundations of contemporary art in your respective regions?

S.R.: In fact, I don’t really believe in doing revolutionary things. I think more about what is necessary in my context, in Hong Kong. For the past four years, the museum has been in a new building, and although we’re still learning from its architecture, there is one space in particular that we’ve been reflecting on for some time. It’s a very large space, an atrium, that the Artistic Director and Chief Curator, Doryun Chong, and I find particularly interesting. However, since we felt we needed someone to help us think through it, program it, and intervene in it, a few months ago we decided to invite the Vietnamese artist VietQ—artistic pseudonym of Yan Bo—to work with us over a three-year period to transform that large space into a more intimate one. We didn’t want to simply fill it with big things, but rather to change the dynamics of the architecture. It’s been a wonderful project, very stimulating, and for us, it’s not just an exhibition, but a period of sustained engagement. In addition to working with the museum, with the education team, the programmers, and objects from the collection, he is collaborating with a number of local artists to carry out the project. This is something very enriching, it’s a new working model. So, in my case, I think it’s less about doing something groundbreaking and more about thinking transversally and from different perspectives about the institution: what we need and how we can address that need. We’re not looking to be revolutionary just for the sake of it.

D.C.: Perhaps “shake the foundations” isn’t the right expression. I mean something that hadn’t been done before and that brought about a change in perspective and a transformation in the way we think about, approach, and understand contemporary artistic creation.

R.C.: When I took on the role of Chief Curator of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in 2010, I asked myself: how do I make this museum different? Back in 2001, during a visit to the Venice Biennale, I was struck by the absence of African art. That’s why in 2005, when María de Corral and Rosa Martínez were curators of the Biennale, I tried to get Zimbabwe to participate. However, the timing wasn’t right. Five years later, when I arrived at the National Gallery, I knew this had to be one of our projects. I said: we have to do this. And it was thanks, among others, to Andrea Rose—then Director of Visual Arts at the British Council—whom I had met in London, that we were able to make it happen. She said: “yes, let’s do it,” and that alliance gave rise to a project that has now had eight editions. Although I’ve now passed the baton to Fadzai Veronica Muchemwa, and since 2024 she is in charge of curating the Zimbabwe Pavilion at the Biennale.

On the other hand, when I received the CIMAM Travel Grant in 2022 and was able to attend the Conference, held that year at Es Baluard in Palma de Mallorca, I thought: okay, we’ve taken Zimbabwean art to Venice, but how do we now bring the world to Zimbabwe? It was the informal conversations I had with Mercedes Vilardell—Chair of the Tate’s African Acquisitions Committee and a collaborator on CIMAM’s travel grant program for professionals residing in Africa—during those days that have led to us sitting here today. Looking back, I realize how important those conversations were. They’re the ones that can change perspectives. It’s about how others believe in you and how you believe in what others can do. It’s challenging and expansive programs like those of CIMAM that can truly change how Africa is perceived. Yesterday, Italian colleagues commented that it had been fifty years since Italy last hosted the Conference, but how many years have passed without it being held on the African continent?

S.R.: It’s never happened. But now it will: next year.

R.C.: Sometimes you just have to wait for the right moment.

S.R.: We needed you, Raphael.

R.C.: Well, we needed all of us. That’s how I see it: you can never do it alone. Bringing people together and fostering collective thinking can make a big difference. And I trust that after the 2026 CIMAM conference, many ideas and many things will emerge. It’s important to have these conversations over a coffee, a beer, or a glass of wine, because suddenly one day you realize and think: “well, this is happening.” So yes, I believe it.

We’re not looking to be revolutionary just for the sake of it.

D.C.: I was just thinking about that, how valuable it is to give space to the informal, to let ideas emerge spontaneously and have the possibility of transforming into something much bigger. It seems to me a very current and organic way of understanding the world. In that sense, and to wrap up, could you tell us what you expect, what expectations you have for the 2026 Conference?

R.C.: That informal conversations continue to happen, and to see what comes from them, even if their outcomes are unpredictable. To hear someone say: “it was a conversation I had when I was in Africa, in Zimbabwe,” to hear those stories maybe three, four, or five years later. That someone tells a story about their experience in Africa. As I mentioned, my first CIMAM was in Vienna, when I was still living in London, the second in Palma, and now here we are. It’s all thanks to those informal conversations. And I would love for those conversations to be made visible one day, for there to be another platform that says: “this idea came out of a talk in Zimbabwe.”

S.R.: I couldn’t agree more. And I would say that, if we think about the geopolitics of the current world, what I really hope is that we can continue talking to each other, building friendships, and creating spaces that encourage exchange… That’s what we’re working toward, and it’s something we actively support and build together.

R.C.: It’s always the relationships between people that make the difference, and if we respect them, we can change the world.

S.R.: Yes, I believe that too. Let’s change the world!

D.C.: Thank you so much for this conversation.

Throughout the discussion, various ideas about museums, institutional policies, colonial memory, education, and community practices have been shared. However, for those of us approaching Chinese and African contexts for the first time, there are still many open questions. We aim to truly integrate narratives from Eastern and Global South geographies into our understanding of the global artistic and cultural ecosystem, and to do so we need to begin closing the gap with the real conflicts and tensions that shape them. Starting from notions like participation, community, or change, mentioned throughout the conversation, it’s worth continuing to ask: Can we still speak of “museums” in general terms? How do particular contexts affect the construction of the museum institution? How are the local and the international integrated within a single program? How is that balance found? What factors are considered in shaping collections? And in the exhibition program? How does the international resonate within their discourse? What does it mean to project an artistic identity in a globalized world largely shaped by Western theoretical frameworks?