The reinvention of the museum, from mass tourism to the political trench: "They are not a trophy or a building, they are an activity".

Museums are reinventing themselves as public squares, breaking visitor records and jumping into politics with debates such as decolonization. Their challenges: massification and the temptation to fall into the mainstream.

André Malraux, author of the canonical and philosophical The Imaginary Museum, warned in the 1970s: "Let's be careful with the word museum. It has acquired a halo of luxury, of collection, of necropolis... it seems a bit bourgeois, why not reactionary?". A warning he made once he left the post of Minister of Culture in the era of Charles de Gaulle. At the same time, art critic Brian O'Doherty popularized the notion of the white cube that would dominate the following decades with New York's MoMA as a beacon of modernity.

Half a century later, most museums have outgrown that "halo of luxury", the idea of art storage and the cold white cube. And what happens in 2024? Never before have museums registered such visitor records, from Madrid to Seoul, from Bilbao to Paris. Spanish museums have closed their best year in 2023, a global trend that marks a turning point after the pandemic of covid, while bursting into politics with unusual force with debates such as "decolonization" that drives the minister Ernest Urtasun.

"After the closure and the contraction comes an expansive stage," says Vicent Todolí about the record number of visitors. "Tourism is back and there is a need to make up for lost time. Museums are a way of traveling and also inspire travel," he adds.

Todolí is one of the most outstanding national directors, who headed the IVAM, started up the Serralves in Oporto, directed the Tate in London and now combines his work as director of the Hangar Bicocca in Milan with his orchard in Palmera (Valencia), where he grows 400 varieties of citrus fruits. The downside of the spectacular figures -such as the 3.3 million at the Prado or the 1.3 million at the Guggenheim, in a city like Bilbao, with a population of barely 350,000- are the long queues and crowded halls, a common sight in certain blockbuster exhibitions. Museums also become overcrowded.

"The museum is not a trophy or a building: it is an activity," Todolí warns about the danger of falling into the mainstream that affects the great ones. "It can be in a cabin or in an abandoned factory, in fact, for me they are the most interesting spaces. When the commercial becomes an objective, instead of serving art, which is its mission, the museum serves art."

Because in Spain there are more than 1,500 museums scattered throughout the country, from the remote Natural Park of Los Barruecos, in Cáceres, with the surrealist Vostell Museum, to the new Museum of the Baroque, which opens on February 21 in Manresa, capital of a county with 78,000 inhabitants (where Rosalía bought her modernist mansion).

From elitism to ethics, the mantra of today's museums is proximity, participation, inclusion and a long list of concepts up to the definition of the museum as a "place of shared creation", as claimed at the last congress of the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art (CIMAM), held in November in Buenos Aires. For the first time in its history (the association was founded in 1962 and brings together the world's major museums), the convention focused on the social role that every art center should play. And the main examples came neither from Europe nor from North America, the West that has dictated the artistic canons, but from Latin America.

"The museum is not a trophy or a building: it is an activity. It can be in a hut or in an abandoned factory."

Vicent Todolí

"Latin American museology today has some key contributions compared to international museology," says William Lopez, director of the National Museum of Colombia, one of the oldest in the Americas, which has just celebrated its bicentennial with a critical and reflective exhibition that questions the myths of the formation of the nation after its independence. "The Social Museology network of Rio de Janeiro, the community museums of Mexico, Peru and Chile.... We come from painful contexts, of inequalities, discrimination and violence. But at the same time they are very creative and resilient, which makes us porous institutions and attentive to the collective vibration. It allows us to survive as societies.

His museum has given a voice to the traditionally excluded: Afro-descendants, peasants, indigenous communities (who now star in the year-long exhibition Acción indigenista), rappers and graffiti artists from the communes (in the acclaimed exhibition Nación hip hop). Particularly in Colombia, art is not detached from violence. "The fact that we have been living in war practically since the 1960s means that cultural institutions cannot turn their backs on this crossroads. From the museums we have to attend with courage and in a very lucid way to the humanitarian and symbolic dimensions of the conflict," says Lopez.

Something that materializes in the Fragments counter-monument, whose metal floor was built with the more than 37 tons of weapons that the FARC surrendered in 2016, after the peace agreement reached with the government. Doris Salcedo, one of the country's most important artists, projected in downtown Bogota this space of memory, a living architecture in which other creators exhibit their projects, always related to political violence, and which is managed by the National Museum. "From the museum we respect the autonomy of Fragments to the maximum, whose objective is that of a symbolic reparation for the victims," says Lopez.

Can you imagine the Reina Sofia or MoMA guarding a 9/11 or 9/11 memorial with temporary exhibits on terrorism and peace? This is what is happening in Bogota. And visitors do not leave indifferent: a small zen bamboo garden with a bench allows them to rest and process what they have seen inside, as in a kind of collective mourning. "We think of the visitor as a politically critical subject," emphasizes the director.

If Latin American museums focus on responding to the most immediate problems of their environment, European museums are immersed in a series of intellectual and thematic debates that are repeated in exhibitions and biennials. For Vicente Todolí, the art world "moves in a pendulum-like fashion: there are issues that grab attention and then give way to others". "In the globalized world there ends up being a lot of uniformity," he reflects. "At first there was talk of styles, then of movements and now of trends. In two or three years new debates will emerge, it's going faster and faster, in line with our consumption habits, which are very fast."

"Instead of being a platform for cultural and unidirectional domination, museums can be a space for liberation and emancipation."

William Lopez

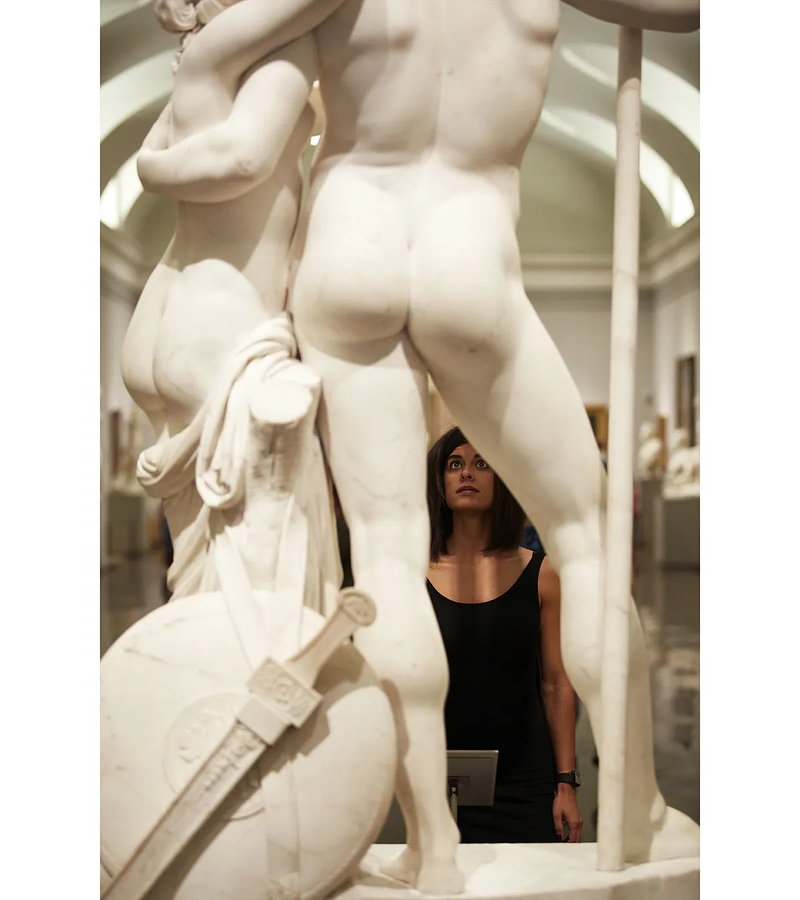

Current debates can be summarized in five axes: sexual and gender dissidence (usually the artistic lexicon applied to queer and the LGTBI community); feminism and the representation of women's bodies; the environment and the future of the planet; the vindication of the indigenous, migrants and marginalized communities; and, of course, decolonization. Not that these are novelties. In 1989 the Guerrilla Girls already stood up in front of the Metropolitan with a performance shouting "Do women have to be naked to enter the Met?" and handed out posters and leaflets denouncing that less than 5% of the artists exhibited in the Modern Art sections were women, but 85% of the nudes were female.

And yet, these are the trends that will continue in 2024. This spring, they will hatch at the Venice Biennale, the great showcase of contemporary art, whose leitmotif is To Be Foreign. The United States will send for the first time a representative with indigenous roots (Jeffrey Gibson, half Cherokee and Choctaw), Spain will also opt for the first time for an artist not born in the country (the Peruvian Sandra Gamarra, based in Madrid, will focus on the consequences of Spanish colonization in her Pinacoteca migrante), Ireland will bet on queer with the artist Eimear Walshe...

"There is a false idea of progress in the art world," warns Fabián Cháirez, a Mexican artist who subverts gender stereotypes. "With the spread of social networks and the Internet, public opinion is stronger and demands more diversity in art centers. To look more avant-garde, many institutions integrate certain themes in a superficial way, without real knowledge and conviction. It's a masquerade," criticizes Cháirez, who has become one of the LGTBI voices in a country where it is not always easy to "live openly homosexuality. He hasn't been exhibiting in Mexico for two years, but he has been in Europe and particularly in Spain: in 2023 he was in Madrid and now he brings to Barcelona the exhibition Las Plumas ardiendo al vuelo, at the Imaginart gallery.

"There is a desire to wash our image, what they call pink washing. LGTBI artists are pigeonholed in the month of Pride, but we exist all year long! And we are a reflection of society, it is also necessary to think from our point of view", he claims. Five years ago, one of his works caused a real stir, with demonstrations that reached the point of violence in front of the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico. The reason? The Revolution or Emiliano Zapata on the back of a white steed, naked, wearing stilettos and a pink hat. Popularly renamed the Gay Zapata it unleashed the wrath of the Farm Workers Union, which demanded its removal for "denigrating" the figure of the revolutionary hero. "Masculinity is sacred," sighs the artist. And he gives as an example the controversy that has unleashed the poster for Holy Week in Seville, with the Christ of Salustiano Garcia that, for some, looks like a gay icon. "When these controversies occur, it becomes evident how conservative and patriarchal our societies continue to be: there are sacred totems that cannot be touched," says Cháirez.

"A museum cannot be defined in a single word, each one is a world. A painting museum is not the same as an archaeological museum or an audiovisual museum."

Enrique Sobejano

Just a week before the Christ controversy, the scandal that made all the headlines was Minister Ernest Urtasun's decolonizing proclamation to "overcome a colonial framework or one anchored in gender or ethnocentric inertias," without a concrete proposal on how to decolonize national museums. "It is a job that has to be done. And it will be done. Just as works of art plundered by the Nazis have been returned, although there are still open trials," Todolí compares. From Mexico, Cháirez considers that the return of pieces "is a symbolic gesture to be applauded, but it has to go further, with a real reparation and cultural exchanges". From Colombia, William Lopez advocates "not to dehistoricize the past or the very history of exhibition spaces," a strategy followed by the Museum of Africa in Brussels, explaining to its visitors the provenance of the works. Quoting sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Antonio Gramsci, Lopez adds: "Instead of being a platform for cultural and unidirectional domination, museums can be thought of as a space for liberation and emancipation.

The museum as a physical space is one of the issues that has changed the most in recent years: its architecture. "Compared to other buildings, museums have a very specific raison d'être: to protect, exhibit and disseminate pieces and objects, whether they are art or not. But they can no longer be mere containers. They have to generate public spaces in the city, in the landscape, in the place where they are located," says architect Enrique Sobejano, who founded his studio in 1984 with Fuensanta Nieto. In recent years they have become one of the Spanish firms that has designed and reimagined the most art centers: the impressive Arvo Pärt center in the middle of a forest in Estonia, the Cité du Théâtre in Paris, the Archaeological Museum in Munich, the Archive of the Avant-Garde in Dresden, the C3A in Cordoba, and so on and so forth, with more than thirty examples.

"A museum cannot be defined in a single word, each one is a world. A painting museum is not the same as an archeological museum or an audiovisual museum.... Each one requires different answers," says Sobejano. Now they are immersed in the remodeling of the large 40,000-square-meter Dallas Museum of Art, a competition they won in 2023, beating American firms or star architects like David Chipperfield, and which illustrates the architectural paradigm shift from the 1980s to today. "It's a recent building. It is not that it has become obsolete, but it is precisely about changing the concept of the museum of the 80s. The building is very hermetic and closed, it responds to the idea of a container for practical reasons: when it was built, the area was full of industrial buildings. Now in Dallas everything is public and open spaces. And the museum has to be, too," explains the architect.

In 2008, Nieto Sobejano received the National Restoration Award for innovative solutions to rehabilitate or expand a building, creating squares, gardens, new agoras. "In architecture, very clear typologies had been defined as to what is the most appropriate building for a library, university, museum, archive.... But they are becoming more and more permeable and there are fewer limits between them," Sobejano points out.

And the museums of 2024 are already those public squares.